Parenthood, especially for first-time parents, can feel tough. A lot of that shows up in the little moments of worry, like the extra calls to your pediatrician, quick texts to experienced parents, or questions for your childcare staff about what is “normal.” If you want to reduce some of that anxiety and better understand how infants grow and learn in early childhood, it helps to look at Parten’s six stages of play.

One of the earliest stages you will notice is the solitary play stage. In the solitary play stage, a child plays on their own, fully focused on what is in front of them, even when other children are nearby. In this blog, we will break down one of the six stages of play-based learning, solitary play. We dive into what solitary play looks like, why it matters for a child’s development, and how you can support it in simple, practical ways at home or in a childcare setting.

What Is Solitary Play?

Solitary play is when a baby or young toddler engages in independent play and stays focused on what they are doing. In this stage, children engage with toys, objects, or simple solitary activities without trying to involve other children.

In Parten’s stages of play, solitary play is one of the earliest stages you will notice in early childhood. It is very common from 0–2 years because children begin by learning basic skills like grabbing, shaking, banging, dropping, and watching what happens next.

You might see independent play in these ways:

- Shake a rattle again and again to hear the sound

- Drop a toy, look for it, then drop it again

- Stare at a high-contrast book or picture and turn pages (even if they turn them “wrong”)

- Put objects into a container and take them out

- Stack building blocks, knock them down, and repeat

- Push a toy car back and forth without trying to “play with” someone else

In infants, solitary play may last only for short bursts. That is normal. As toddlers grow, these solitary play moments often get longer, especially when the activity matches the child’s age, interests, and different toys they are curious about.

Note: Solitary play is different from unoccupied play, where a child starts out not really playing yet and may seem to be watching, wandering, or figuring out what to do next. It is also different from onlooker play, where a child watches other children play and learns by observing before joining in.

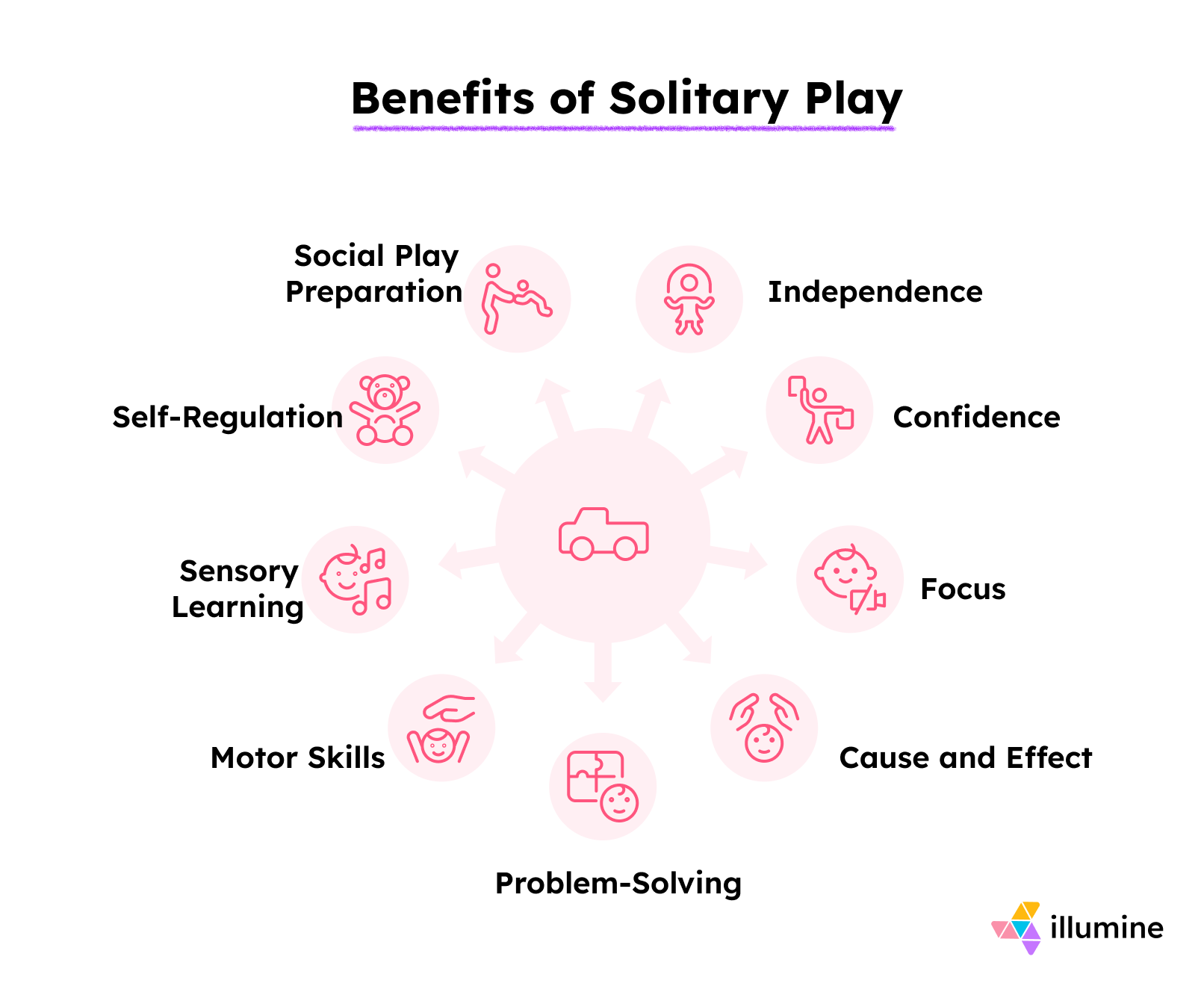

Why Solitary Play Is Important

Solitary play may look quiet and simple, but a lot is happening under the surface. Solitary play is an integral part of early childhood development, because it helps children develop important skills that support confidence, future learning, and healthy routines.

- Builds independence: Your child learns to explore freely and try things without needing constant help, which supports self discovery.

- Boosts confidence: Small “I did it” moments add up, making kids feel capable.

- Improves focus: It helps babies practice attention, even if it starts with short bursts.

- Teaches cause and effect: They learn what happens when they shake, drop, push, or pull something.

- Supports problem solving skills: Trial-and-error play strengthens early cognitive skills and supports cognitive development.

- Develops motor skills: Grasping, reaching, stacking, and “in-and-out” play strengthen gross and fine motor skills.

- Encourages sensory learning: Kids explore textures, sounds, and movement in a safe, self-led way.

- Helps with self-regulation: Repetitive play teaches self regulation and helps manage intense emotions.

- Supports self reliance: Over time, children learn they can start, continue, and finish a play task on their own.

- Encourages self expression: Solitary play lets toddlers try sounds, actions, and early pretend in a way that feels low-pressure.

- Prepares for social skills later: Skills like focus and exploration support social play in later stages, like when a child plays alongside peers, and eventually moves into associative play and cooperative play.

Age-Appropriate Examples Of Solitary Play

Below are simple, real-life examples of solitary play, grouped by age, so it is easy to picture what “normal” can look like. These solitary activities support a child’s development in early childhood and build a base for future learning.

How To Support Solitary Play in Infants and Toddlers

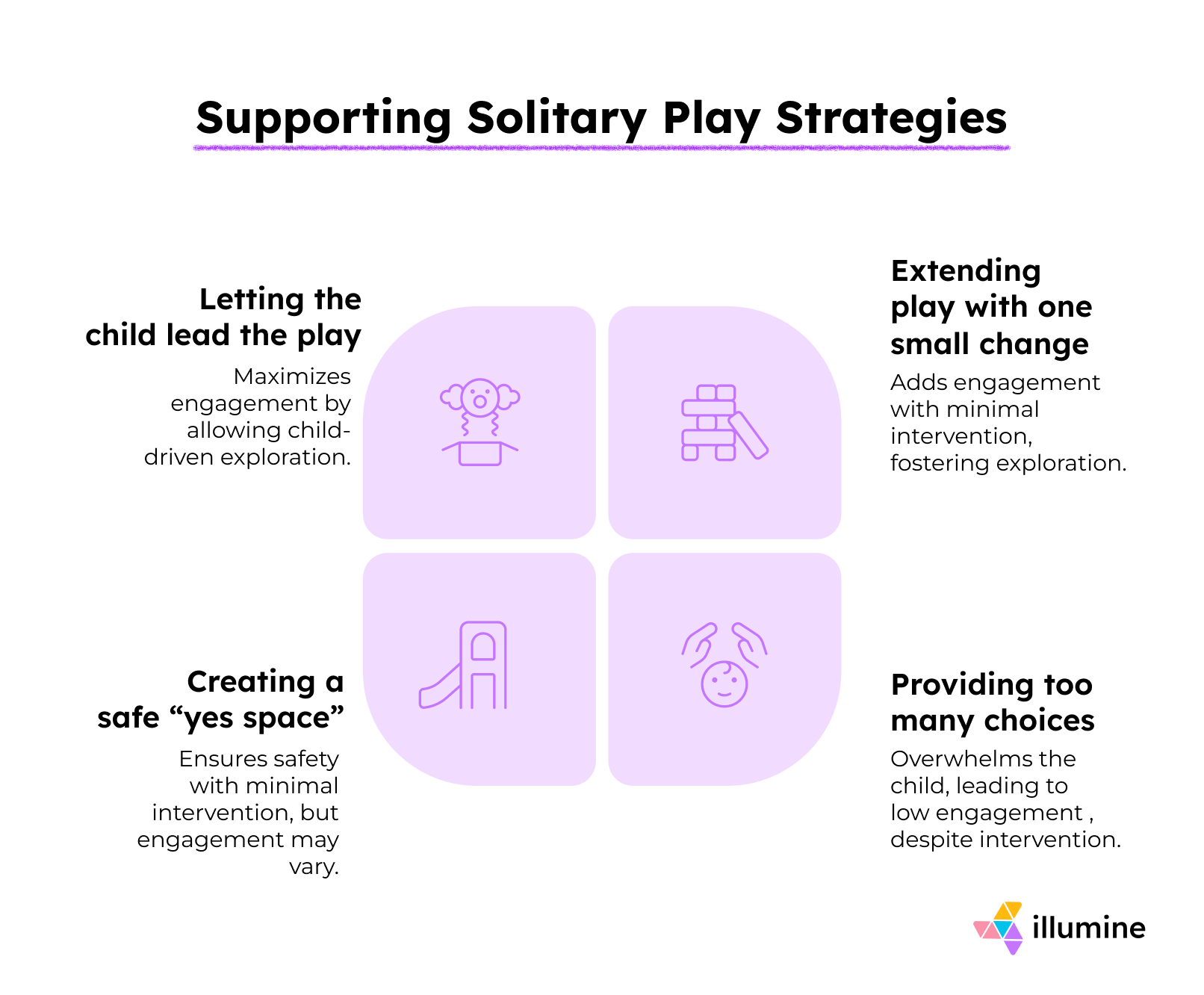

Many parents support solitary play without realizing it, and many also accidentally interrupt it because they want to help. If your baby is quietly exploring, that is not boredom. That is learning. Supporting solitary play is mostly about knowing when to step back and when to step in.

It can also help to remember that play preference changes by day and setting. Some children like to play independently for longer, and some prefer quicker play scenarios with more adult interaction, and both can be normal.

The tips below will help you set up the space, choose the right materials, and respond in a way that keeps your child engaged without taking over, even when other children are around.

- Create a safe “yes space.” Set up one spot where your child can move and explore freely, so you do not have to stop them every few seconds. Use a mat or playpen, cover sharp corners, and keep choking hazards out.

- Offer fewer choices at a time. Put out 3–5 items only; too many toys can overwhelm babies and toddlers, and they end up hopping from one thing to the next without real play.

- Rotate instead of buying more. Keep most toys in a box and swap a few every few days; “new to them” often brings longer focus without adding clutter.

- Use open-ended materials. Blocks, balls, scarves, nesting cups, and containers invite more exploration than single-use toys because a child plays with them in many ways.

- Match the activity to the age. If it is too hard, your child gets upset; if it is too easy, they lose interest fast. Aim for “a little challenge” like a simple posting toy or a large-piece puzzle.

- Let your child lead the play. Place the toy in reach and watch what they do first; the goal is not to show the “right way,” but to support self discovery.

- Pause before you help. Give them a few seconds to try, adjust, and try again; those small struggles are where new personal skills and confidence build.

- Stay close, but do not take over. Sit nearby for supervision and comfort, especially for infants, but avoid constant directions like “Do this” or “Try that,” which can break their focus.

- Use short narration instead of questions. Say what you see in one line (“You dropped it,” “You opened it,” “You’re stacking”) so you support language without turning play into a test.

- Extend play with one small change. Add one new container, one extra block, or a spoon for scooping, then step back again; small additions keep play going without shifting the whole activity.

- Support frustration with tiny hints. If they are stuck, model once or help with one step, then hand it back so they still feel in control of the play.

- Respect short attention spans. Babies may play for under a minute, toddlers for a few minutes; let them stop and return later instead of trying to “make them finish.”

- Avoid interrupting repetitive play. Repeating the same action is how young children learn and teaches self regulation; as long as it is safe, let them repeat.

- Balance solo play with connection time. Solitary play works best when your child also gets plenty of talk, cuddles, and back-and-forth interaction during the day.

- Reduce background distractions. Turn down the TV and loud noise during play windows; a calmer environment makes it easier for toddlers to stay engaged.

Conclusion

Solitary play does not need fancy toys or complicated activities. What matters most is the setup: a safe space, a few age-right materials, and enough time for your child to enjoy their own company without being interrupted. Your role is simple. Stay nearby, observe, and step in only when your child truly needs help. The goal is not to speed up learning, but to give your baby the chance to practice focus, problem-solving, independence, and self reliance in small, natural ways that support child’s growth, cognitive development, and future learning.

In time, many children move from solitary play into social play and group activities, including stages like parallel play, associative play, and cooperative play.